Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

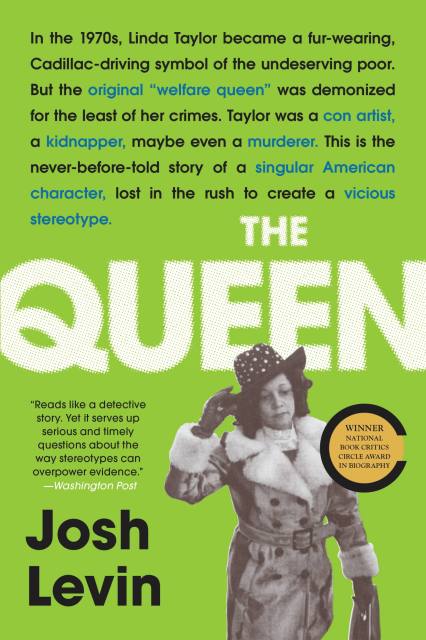

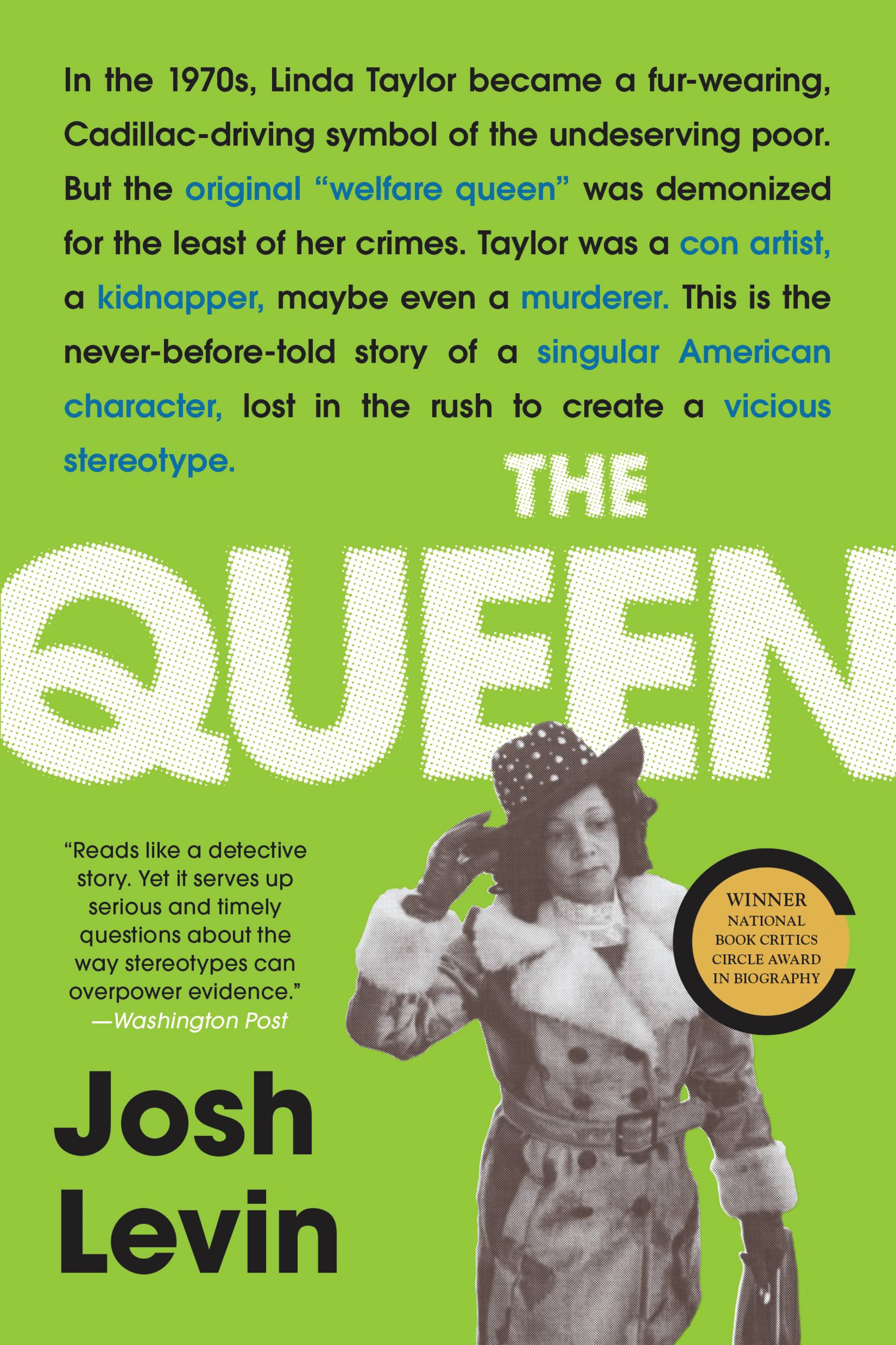

The Queen

The Forgotten Life Behind an American Myth

Contributors

By Josh Levin

Formats and Prices

Price

$12.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 21, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award in Biography

In this critically acclaimed true crime tale of “welfare queen” Linda Taylor, a Slate editor reveals a “wild, only-in-America story” of political manipulation and murder (Attica Locke, Edgar Award-winning author).

On the South Side of Chicago in 1974, Linda Taylor reported a phony burglary, concocting a lie about stolen furs and jewelry. The detective who checked it out soon discovered she was a welfare cheat who drove a Cadillac to collect ill-gotten government checks. And that was just the beginning: Taylor, it turned out, was also a kidnapper, and possibly a murderer. A desperately ill teacher, a combat-traumatized Marine, an elderly woman hungry for companionship — after Taylor came into their lives, all three ended up dead under suspicious circumstances. But nobody — not the journalists who touted her story, not the police, and not presidential candidate Ronald Reagan — seemed to care about anything but her welfare thievery.

Growing up in the Jim Crow South, Taylor was made an outcast because of the color of her skin. As she rose to infamy, the press and politicians manipulated her image to demonize poor black women. Part social history, part true-crime investigation, Josh Levin’s mesmerizing book, the product of six years of reporting and research, is a fascinating account of American racism, and an exposé of the “welfare queen” myth, one that fueled political debates that reverberate to this day.

The Queen tells, for the first time, the fascinating story of what was done to Linda Taylor, what she did to others, and what was done in her name. “In the finest tradition of investigative reporting, Josh Levin exposes how a story that once shaped the nation’s conscience was clouded by racism and lies. As he stunningly reveals in this “invaluable work of nonfiction,” the deeper truth, the messy truth, tells us something much larger about who we are (David Grann, #1 New York Times bestselling author of Killers of the Flower Moon).

Genre:

-

Longlisted for the PEN/Jacqueline Bograd Weld Award for BiographyTheRoot's Favorite Reads of 2019 Washington Post's 50 Notable Works of Nonfiction Boston Globe's Best Books of 2019Buzzfeed's Best Books of the YearMother Jones's Favorite Books of 2019The National Book Review's Ten Best Nonfiction Books of the YearStar-Tribune's Best Nonfiction of 2019NPR Code Switch's Holiday Book Guide New York Times Book Review Editor's Choice PickChicago Public Library Best Books of 2019Crimereads's Best True Crime Books of 2019PopSugar's 45 Best Nonfiction Books of 2019Book Riot's 50 Great Books about True Crime Inspired an Esquire Best Podcast of 2019

-

"The Queen: The Forgotten Life Behind an American Myth reads like a detective story. Yet it serves up serious and timely questions about the way stereotypes can overpower evidence."Lisbeth B. Schorr, Washington Post

-

"Another author would have used the 'welfare queen' as a jumping-off point to explore stereotypes, welfare politics and political rhetoric. Levin addresses all that, but his real goal is to put a face to Reagan's bogeywoman, tracking every alias, every scam, every duped husband and every dodged arrest. He presents Linda Taylor not as a parable for anything grand, but as a singular American scoundrel who represented nothing but herself...Part of the fun of Levin's book is burrowing inside his obsessive quest."Sam Dolnick, New York Times Book Review

-

"A deftly drawn, quick-paced police procedural...The Queen is a story of grand scale manipulation, both of Taylor's trail of brazen deceptions but also the role media and politics played in shaping a narrative - making all of us the victims of games of shadows and smoke."Lynell George, LA Times

-

"Riveting."Gene Demby, NPR

-

"In re-examining the 'welfare queen' myth, Slate's Josh Levin tells a story about racism in America and the oversimplified narratives that still dominate political discourse."Laura Pearson, Chicago Tribune, 25 Hot Books of the Summer

-

"Levin's work succeeds at untangling a complex life, both the actual facts of it - no easy task for a woman with dozens of aliases - and what she ultimately came to represent."Kate Giammarise, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

-

"The verve and humor of Levin's writing mirrors the brazenness of the crimes Taylor committed...Taylor is like a one-person, low-rent "Ocean's 11,"and you can't help but marvel at the ingenuity with which she kept it up for decades. Neither can Levin, who ends virtually every chapter with a cliffhanger, tantalizing us with clues to Taylor's next big scam. But there's a bigger, and grimmer, story here, and Levin gives it its due."Chris Hewitt, Minneapolis Star-Tribune

-

"Levin tells this story with a forceful combination of empathy and rigor... The Queen is a powerful reminder to ask what stories lie behind the ones that catch the public eye."Washington City Paper

-

"Levin has managed to bring the human being out from under the stereotype. He does so in clear, concise writing that refrains from overwrought editorializing...Levin succeeds in always drawing readers back to his main subjects: systemic oppression, the rhetoric that feeds it, and how Taylor fits into both."Ilana Masad, NPR.org

-

"In his great work of investigation, Levin, who is editorial director of Slate, uncovers this [welfare queen] creation myth and argues that it hardened into a stereotype deployed to chip away at benefits for the poor. Levin has written a fascinating tale of how the myth was constructed, but he has also dug deeply into Taylor's story, revealing her as to be a grifter, a thief, and possibly a murderer - a woman who was victimized, but who also victimized those more vulnerable than she."National Book Review

-

"[Levin's] portrait of [Taylor] is unflinching; so is his portrayal of the demagogues who profited from her story."Boris Kachka, Vulture's 8 New Books You Should Read This May

-

"There is something uniquely special about a work that sets out to re-examine the origin of an American social trope-the original "welfare queen"-and results in such a meticulously researched book that both complicates ideas of race and class many previously took for-granted and reads like one of the most outlandish true crime capers of the season."Allison McNearney, The Daily Beast's Best Summer Beach Reads of 2019

-

"Highbrow + brilliant"New York Magazine, Approval Matrix

-

"The woman's name was Linda Taylor. And a new book, "The Queen" by Josh Levin demystifies who she was. Turns out her most egregious crimes had nothing to do with welfare scams...But those crimes didn't fit the lazy, trifling welfare narrative...By page 40 my mouth dropped at the audacity of con-artist Taylor. Levin, an editor at Slate, spent six years piecing together the life of a woman whose image demonized black women. She eventually dropped out of public sight and Levin's compelling narrative weaves Taylor's story inside public policy."Natalie Y. Moore, The Chicago Sun Times

-

"Levin's story of Taylor, who went under numerous aliases, is an extremely well-researched and well-written account of her life and misdeeds, and of the glory-seeking legislators, prosecutors and reporters who were so quick to see a good headline and just as quick to ignore real malfeasance such as kidnapping, selling of children and almost certainly murder - times three. ... Levin spent six years researching Taylor, and The Queen is an excellent account of her life, her criminal activity and the politics of blame still with us today."Chris Smith, Winnipeg Free Press

-

"This is a highly recommended, fascinating examination of a prolific con artist, who by the end of her life may not have been able to distinguish between reality and her own lies."Library Journal, starred review

-

"In his book The Queen, journalist Josh Levin tells the life story of this footnote character in American political history, and finds that the crime for which she is remembered was just a minor incident in a life of theft and deception."Edward McClelland, Chicago Magazine

-

"Impressive in its dedication to nuance and proper context."Boston Review

-

"It's about Linda Taylor, the 'Cadillac-driving welfare queen in Chicago'' that Pres. Reagan referenced in a 1983 speech about rampant defrauding of government anti-poverty programs...Her story helped popularize stereotype about lazy Black people on the dole...But the focus on her welfare grifting meant people mostly ignored the more sinister crimes she was implicated in - like kidnappings and murders! Anyway, it's a wild book."Gene Demby, NPR Books

-

"The Queen is a rich character-study of a complicated black woman that Levin rescues from simplistic stereotyping. It's also an at study of the ways black women have been demonized in society."Bridgett Davis, The Millions

-

"Levin's book is a moral seesaw. It's tempting to feel sympathy for Taylor, born into a society and a class calibrated to beat her down. Gaming the system is every American's dream, and Taylor achieved it with stunning ingenuity."The Nation

-

"The strength of The Queen lies in Levin's meticulous scouring of the historical record to paint a picture of a woman who was infuriatingly difficult to pin down during her lifetime, resurrecting a biography of the person who would become the ur-welfare queen. By examining her reality, we can finally question the very concept of a welfare queen and deconstruct a myth spun out of selective details."The New Republic

-

"In the finest tradition of investigative reporting, Josh Levin exposes how a story that once shaped the nation's conscience was clouded by racism and lies. As he stunningly reveals, the deeper truth, the messy truth, tells us something much larger about who we are. The Queen is an invaluable work of nonfiction."David Grann, #1 New York Times bestselling author of Killers of the Flower Moon

-

"The Queen is a wild, only-in-America story that helped me understand my country better. It's a fascinating portrait of a con artist and a nation... and the ways the United States continually relies on oversimplified narratives about race and class to shape public policy, almost always at the expense of brown people and poor people."Attica Locke, author of the Edgar Award winning Bluebird, Bluebird

-

"For decades, Linda Taylor has been demagogued by politicians and the press, reduced to a cruel stereotype: the welfare queen shamelessly leeching from government coffers. Through meticulous reporting, Josh Levin's The Queen illuminates in full the story of a life far more complicated, cunning, criminal, tragic and fascinating than the historical stereotype would have ever allowed us to see."Wesley Lowery, author of They Can't Kill Us All

-

"It is impossible to read The Queen without pausing every few pages to marvel at either the brilliance of Josh Levin's research or the sheer wildness of the tale. By pouring years of devotion into piecing together Linda Taylor's bizarre criminal odyssey, Levin has created a work of American history like no other-an enthralling portrait of a nation whose splendid promise has too often been distorted by prejudice and political cynicism."Brendan I. Koerner, author of The Skies Belong to Us and Now the Hell Will Start

-

"While the story of Linda Taylor is at once bewildering and tragic, there are millions of untold stories of people who suffered because of her infamy, and we may never know their names. But by reading about Taylor's life and the perplexing person she was, we may be able to understand people who live today in poverty. We can meet their challenges with compassion, and not lionize or demonize them, but see them as Linda was never seen in the eyes of the public-as a full person."Southside Weekly

-

"A presidential campaign, constructed from a scaffolding of bigotry. Unbridled backlash against the poor. Ideological agendas paving over the truth and ignoring real victims. Josh Levin's The Queen is both an unforgettable story and a vital way of understanding how we got to our current political crossroads. This is a crucial, important book."Robert Kolker, author of The Lost Girls

-

"Josh Levin's delicious deep dive into the true story of Ronald Reagan's welfare queen unwraps a bizarre and entertaining yarn of a grifter's journey through the infernal levels of racism, sexism, sensational journalism, slipshod law enforcement, and the twisted family values that brought us from 20th-century America to where we are now."Robert Lipsyte, author of SportsWorld: An American Dreamland

-

"An upcoming biography by journalist Josh Levin about Linda Taylor, the Chicago woman whose complicated story was demonized and manipulated by politicians and press (namely, the Chicago Tribune, according to Levin's account) until she was Ronald Reagan's infamous 'welfare queen'...It's tempting to describe Levin's masterful book as alternate history of 1980s Chicago. But no - again, it's this Chicago, on this planet, not twisted on its head, only righted."Christopher Borrelli, The Chicago Tribune

-

"Josh Levin's account of the bizarre life of the woman who became known as "the welfare queen" is a triumph of research, insight and evenheadedness...January LaVoy narrates this multilayered biography with clarity and compassion."-Washington Post, audiobook review

-

"Levin nimbly explores Taylor's life in a story that becomes more complex the more it's revealed...As the author shows in this excellent piece of true-crime writing, Taylor's case is entirely rare, but the potent political symbolism it inspired certainly did no favors to those who truly needed welfare assistance in the years since"Kirkus, starred review

-

"Levin, the national editor of Slate, writes a stunning account of Linda Taylor, the woman famously tagged as a "welfare queen" in the 1970s. His powerful work of narrative nonfiction...demonstrates how a single distortion can ruin lives...Levin does a terrific job of balancing his portrait of a criminal, of the racism of police who didn't bother to solve the three murders connected to Taylor, and of the widespread stereotyping of Blacks that grew out of her crimes and a president's distortions."Booklist starred review

-

"Slate editorial director Levin's dogged investigative work in his impressive debut reveals...the stranger-than-fiction story of [a] woman who called herself Linda Taylor (among numerous other names)."Publishers Weekly

-

"A jaw-dropping, just astonishing feat of reporting...the sensitivity with which he writes about [Linda Taylor's] childhood and history...is fascinating."Slate's Culture Gabfest

-

"In The Queen, Slate editor John Levin takes a holistic approach to Taylor's story, relaying the details of her early life, her crimes, and her unexpected turn as a national debating point, exposing some uncomfortable truths about the era's attitudes, so many of which persist today."CrimeReads, The Best Crime Non-Fiction Books of May 2019

-

"Levin, an editor at Slate, returns us to a former era of uproar...in doing so complicating political and cultural debates that have survived to this day."Talya Zax, The Forward

-

"Levin writes with sympathy. Themes of rejection, racial confusion and possible mental illness create a strong undercurrent beneath this fascinating story."Alden Mudge, BookPage

-

"A compelling new look at Linda Taylor...The Queen is a cross between true-crime story, biography and political history."Shelf Awareness

- On Sale

- May 21, 2019

- Page Count

- 432 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316513272

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use